Nutrition is necessarily related to metabolism, because what you eat is what fuels the metabolic processes that make everything happen in your body. It is both extremely simple, and hideously complex at the same time.

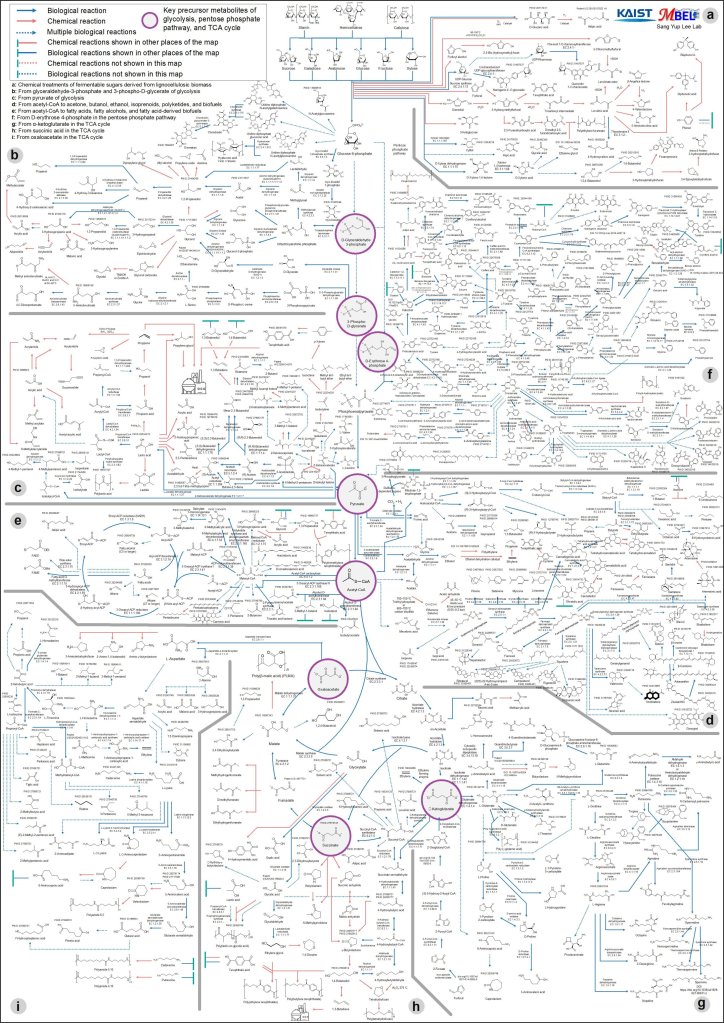

First, a snapshot of the complexity:

This is just one version of a small part of what we know about cellular metabolic processes, and it’s always changing, as we discover new enzymes, new pathways, and new genes. Next time someone says to you, “If only you put more [fill in the blank] in your diet, or take this supplement, it will solve all your problems,” think of this diagram, and then tell them, “that’s not how any of this works.”

This is not to say that taking a specific supplement, in a specific situation, to solve a specific problem is a waste of time. If you have, say, osteoporosis (bone weakening due to demineralization), then supplements like Vitamin D, calcium, and phosphorus may be indicated, as well as other medications. But that’s solving a specific problem, not a cure-all wonder pill or potion.

Okay, now the easy stuff. Like all living systems, your metabolism is governed by the iron Laws of Thermodynamics. The First Law says all the energy going into a system will equal the energy out, plus (in the case of living systems) the increase of the mass of the system (growth). Put another way, the energy in (food) will result in either activity (movement or operations of the body) plus the growth of the body (new tissues, or stored energy in the form of fat).

The Second Law says that every time energy is transformed from one type to another, a little bit is lost in the form of heat. So, the full situation for diet and metabolism is this:

Calories In = exercise/activity + growth/weight gain + heat = Calories Out

That heat is what we use to maintain our body temperature, because we are a type of animal called homeotherms (maintains constant body temperature regardless of external environment).

Keeping that in mind, it would seem that dieting and weight control is a simple matter of calories in and calories out, either eat less or work out more. Well, sort of. Turns out, even though the First Law of Thermodyamics says that, in reality, there’s a lot more; a lot, lot, lot more to it.

First, let’s look at children as compared to adults. Children have higher metabolic rates generally (they burn more calories per hour, all other things being equal) because they are smaller (math involved, we’ll skip it), AND they are growing like crazy. They are converting a large portion of their calories into new bone, muscle, skin, nerves.

But for us adults, we only need calories for basic operations, maintenance and repair, and exercise. That’s it. Anything extra, and you start gaining weight. How you gain weight is a result of your genetics and your lifestyle. Between the two, genetics plays a far larger role than we appreciate. This is where you get different body types, and different responses to the inevitable holiday binge. Why are we so different from each other when it comes to metabolism? Let’s look at a small portion of that chart again.

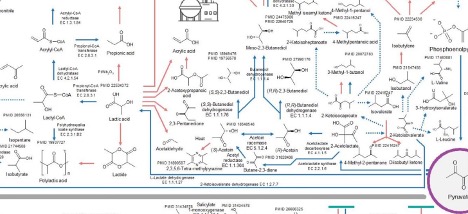

The purple circle in the lower right is pyruvate (bad cropping, sorry), one of the molecules glucose is broken down into. Cells generate energy by breaking glucose down into a series of molecules, each step releasing more energy. Pyruvate is one of them.

Quick detour on metabolism terminology: all these processes involve molecules of different shapes and sizes, which are either taken apart to release energy, or put together, either to transform them into something else, or to store energy. The molecule transformations are either done to build something, like tissues, or to create a new pathway to release energy in a different way. There are thousands and thousands of these pathways, and we find more all the time.

Glucose is the universal gasoline of the body, a form of energy which all cells need to do their work. Your glucose, or blood sugar, is the thing that when it goes low, you feel run down and can even black out, and when it goes high (for too long) can cause all the problems of diabetes.

Quick linguistics fun fact: the full name for diabetes, diabetes mellitus or D.M. as might be abbreviated in a medical record, comes from Greek and literally means “sweet passing through” referring to the excessive urination that uncontrolled diabetes causes. Again, details for another post, but when your blood sugar goes too high it ends up in the urine and acts as a diuretic, which leads to dehydration (among other things) that can kill you. Why the Greeks were tasting urine is also for another post.

So you take in food, and it either contains starches which are broken down to glucose, or proteins and fats, which are converted (via enzymes) to glucose. Everything ends up as glucose sooner or later, due to all those pathways in the big diagram.

Back to the detail: the blue line leading from pyruvate to the left, ending up at a molecule called lactic acid, represents the enzyme reaction caused by lactate dehydrogenase, or LDH. LDH is a very well-studied enzyme that is found in every tissue, in a variety of forms, throughout the body.

You’ve probably heard of lactic acid, how it accumulates in muscles after strenuous activity, how it causes “the burn”, how you generate more during anaerobic exertion (like sprinting or heavy weight lifting), etc., etc. Well, that reaction goes both ways. LDH also turns lactic acid back to pyruvate, which is yet another source of fuel for the body, as other enzymes take apart and transform the pyruvate molecule to extract more energy.

So what are these enzymes that do all this work? They are little stretches of protein, chains of amino acids, that fold in specific ways to create little shapes, puzzle pieces, that fit very precisely and specifically on the surface of molecules and either help pull them apart, or put them together. An enzyme can take two molecules and “weld” them together, or take a bigger molecule and break it into two smaller ones by breaking a specific joint on the big molecule.

There are thousands and thousands of enzymes, a unique one for every unique chemical reaction in that big mess of a chart. Where do the enzymes come from? The cells make them, each enzyme specified by a unique gene that carries the code to build the protein that forms the enzyme.

Here’s where you can see the first indication of variability between people. Different genetics, different genes, different codes for different proteins, different enzymes that might be better or worse, or work better under different conditions, creating infinite individual variability. But it gets better (as in more complicated).

LDH is actually not one piece of protein, but four different ones, a tetramer. Each one has it’s own gene, and combines with the others to do their job. Right there, you get a lot of different combinations (we’ll skip the math). But it gets even better.

Individual genes aren’t just one and done. They belong to gene families, where a gene coding for a particular protein can have variations in the genetic code that cause small alterations in the amino acid sequence of the protein, which in turn may alter the function of the enzyme the protein folds into. Some variations are “silent” meaning they don’t cause any change (we’ll skip the details). These variations are common and proliferate because they don’t result in any difference between enzymes, and therefore the individual. No basis for natural selection, everyone is equal.

Some variations can cause slight changes, some big changes, some break the protein and cause the enzyme to fail completely. These are the variations that cause disease, or even kill people. Variations are caused by mutations in the genetic code of the gene. Mutations that only cause small changes can be inherited and passed on, spreading through the population. Mutations that kill are wiped out, via natural selection. But they can randomly pop up again. Mutations that only cause a slight change might be the reason someone is a better long distance runner, or why they can tolerate long fasts without getting hangry, or why they store a pound of fat just by LOOKING AT that chocolate mousse.

So how about LDH? How many variations are there in that gene family? Let’s look at just one subunit, LDHA. Right now, and this changes every day, there a thousands of variants in the LDHA gene family that have been identified, and more every day as more genomes are sequenced. Each one producing an enzyme that may have very different properties, affecting a critical step in metabolic pathways in every cell.

Quick summary: genes code for proteins, proteins make the enzymes that control metabolism.

Genes → amino acids → proteins → enzymes → metabolism

The variation of even just one gene family is enormous, and multiplied across the thousands of genes that make up the metabolic pathways in the big diagram at the beginning, which itself is only a partial, incomplete snapshot of what goes on in your cells, and the variety between people is literally infinite.

THAT’S WHY any goofy claim about “if you just take this one supplement” solving your problems (“more energy!”) are a waste of time. Any effort spent wondering about or debating the merits of these supposed “miracle” cures is a distraction, and the more we stand to lose with REALLY understanding what’s going on with metabolism and REALLY solving problems with weight, chronic disease, and keeping people healthy longer.

Leave a comment