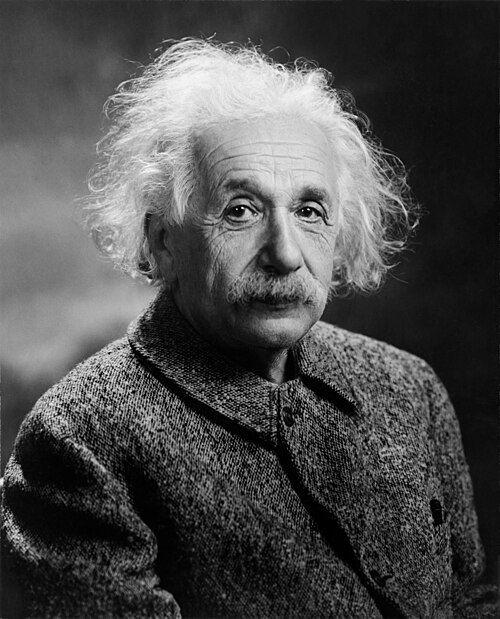

“How have you been, Professor?” Walter Lippmann asked as the scientist approached.

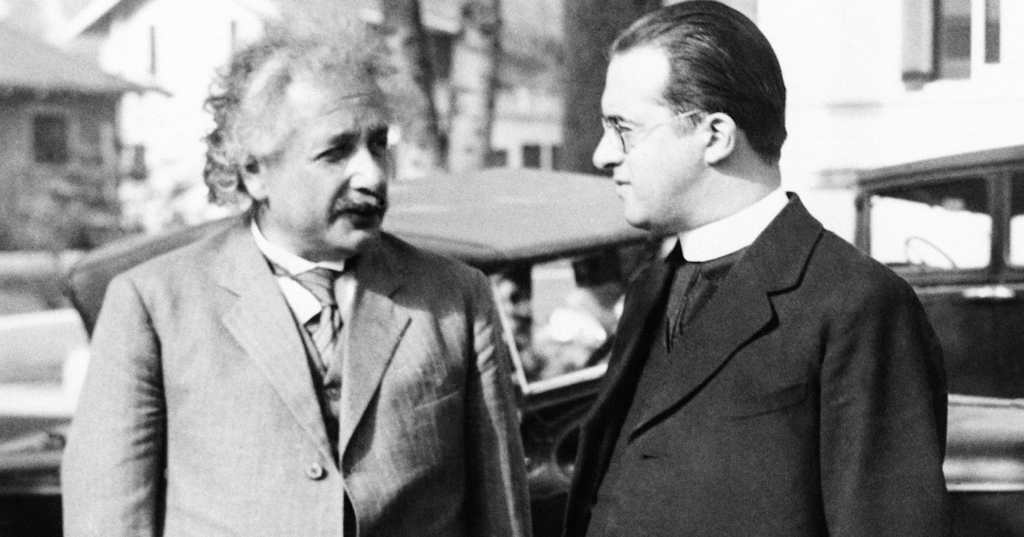

“I am well. Although, I must say it is not so cold and windy down in Princeton!” Lippmann and Fr. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin help Einstein with his overcoat and pull up a third stool. Einstein places his hat on the bar and unwinds his scarf. “But I interrupted your conversation. You seemed to be intent on some very important topic.” The bartender returns with a cup of steaming black tea and places it in front of Einstein. He picks it up with both hands, blows on it, then sips daintily. “So, what have I missed?”

The other two men laugh and begin speaking simultaneously, provoking another laugh. The priest nods at the journalist that he should take the lead, and Lippmann begins the summary.

“We were discussing the limits of human abilities to grasp the scale and complexities of the wider universe. Where Father Teilhard and I differ…”

“Please, just call me Teilhard.”

“Where Teilhard and I differ is what the solution to this challenge is. I believe men of science and good will should take the lead and help steer the public to decisions that further the common good. Teilhard has more spiritual goals in mind.”

The priest turns to Einstein. “My concern with Mr. Lippmann’s approach is who is to judge the agenda of the men of science and their good will? I believe the Church can and should play a role given the concerns with the ultimate destiny of humanity.”

“But is the Church any better a steward of humanity’s destiny than a group of properly educated people of high intelligence?” the journalist replies. “History suggests otherwise.”

The priest nodded. “I am familiar with the Church’s… hmmmm… inconsistent track record dealing with progress. Still, if we are discussing the fate of our species, and of the eternal souls of each individual, then I must insist the Church, as the mediator of Christ’s redemption, is better positioned to lead that effort.”

Albert Einstein followed the back and forth without comment. Lippmann frowned and rubbed his forehead, then sipped his bourbon. “We both agree that the human mind is severely limited in its ability to grasp the enormities of the world around us. Isn’t science better suited to explore and navigate the unknown boundaries to help guide people to better decisions?”

Teilhard nodded and leaned forward. “Science is well suited for discovering new knowledge, that is true. But new knowledge always requires a moral framework, and moral questions are outside science. In addition, science is not infallible. How many scientific theories have been put forward as unassailable truth, only to fall a generation or two later with new data, new ideas, and new explanations?”

Einstein smiled and nodded slowly. “I am familiar with this problem. Let me tell you a story. No, two stories.”

He sipped his tea and the other two men leaned forward.

“I first published the theory of General Relativity in, I think it was 1916.”

“Excuse me, Professor Einstein,” Lippmann interjected, “but where were you at that time?”

“Please, call me Albert. I have no interest in titles. But to answer your question, I was in Berlin.”

“You were able to get this done even despite the war?”

Einstein responded with a rueful smile, giving is shaggy hair a soft shake. “Perhaps it was because of the war. We did what we could to protest, to demand peace, but it was fruitless. So, I threw myself into my work. Maybe too much. I had some severe health problems after the publication. It took a toll.”

“It was a difficult time,” Teilhard added with an arched eyebrow.

Einstein looked at each of them. “You both were involved?”

Lippmann gestured to Teilhard to go first. The priest met Einstein’s gaze.

“I was called up and served as a litter bearer throughout.”

“On the front? As a soldier, not as a chaplain?”

“Several fronts. Ypres, the Marne, Verdun…there were others. Back then, everyone had to serve, even priests.”

“Ach, mein Gott…I am sorry. That must have been awful.”

“It was, but it also led to some of my most powerful insights, about humanity, evolution, and our spiritual journey. It was a very challenging, but necessary, step in my personal development.”

“You met God on the battlefield, eh?” Einstein observed.

“In a sense, yes.”

Einstein nodded. “People often misunderstand my own beliefs on this matter.” He turned to Lippmann. “And you, Mr. Lippmann?”

“I was late to the war. I arrived in France in 1918 and stayed at headquarters. Nothing to speak of.”

“No spiritual revelations?” Einstein said with a wink.

Lippmann shook his head, looking down into his bourbon. “Some political ones, perhaps, but no, nothing spiritual.”

“Well, I’ve had some thoughts on this matter of God.” He turned to Teilhard. “Though I see God in the order of the Universe and the beauty of mathematics, I think you and I probably differ on whether God takes an interest in us on a personal level. I do not believe this, or many other things put forth by organized religions.”

“Perhaps we’re not as far apart as you might think, Albert,” Teilhard responded.

“I must say,” Lippmann interjected, “I’m more than a little surprised to hear two men of science talk so much about God. As Teilhard and I were discussing before you arrived, Professor, I believe our destinies are best determined by the human mind, educated to the highest levels in the sciences, both natural and administrative, and charting our own course free of superstitions.”

“I cannot speak for Father Teilhard, but for myself, I know that science has limits, mostly due to the limits of the human mind. There are questions, important questions, of morality and ethics, that science cannot address.”

Teilhard nodded, and Einstein continued. “For example, the letter we wrote to Roosevelt about the atomic bomb. In retrospect, I have deep misgivings about my role in that.”

“Why is that, Professor?”

“Szilard approached me and insisted I participate, because he did not know the politicians, and he feared they would not take him seriously about the Nazi atomic research. We also did not know for sure just how far along the Nazis were, but we knew some of the scientists involved and what they were capable of. Seeing now what has been unleashed on the world with all the atomic weapons in possession of so many countries, I regret my involvement. It was not certain the Nazis would get a bomb before the war ended, and what we did to the Japanese sickens me.”

“But Professor, someone would have…”

Einstein waved a hand. “I know, I know. Still, my own conscience is troubled by the whole matter.”

They fell silent, then Teilhard leaned forward and put a hand on Einstein’s arm. “You mentioned a story you wanted to tell about relativity.”

“Ah yes, how quickly we can be distracted. Relativity, yes. So, when I finished the equations for General Relativity, one of the implications that stood out to me was that, if all matter exerted gravitational attraction on all other matter, eventually, the entire Universe would collapse in on itself. This troubled me, and seemed counter to what we could observe at the time. So I introduced a variable, called the Cosmological Constant, into the equations. This variable represented a repulsive force to counter the attraction of gravity, and render the Universe stable. But it ended up being a mistake.”

Lippman shook his head in disbelief. Einstein smiled and nodded to Teilhard.

“It was your colleague, Father LeMaitre, who helped show me my error.”

The priest smiled. “You were at first dismissive of him. What did you say? ‘Abominable physics?’”

“Yes, I was too hasty. He is a brilliant man and did wonderful work. He was right, and I was wrong.”

“I don’t understand,” Lippmann said.

“Father LeMaitre, along with Hubble, showed that galaxies far away from our own are receding away from us,” Einstein explained.

“Ah, the Father of the Big Bang. He’s all over the papers. Quite popular,” Lippmann observed.

“Yes, exactly. The Pope seems to be very fond of him, eh, Teilhard?”

“It seems some ideas are more compatible with current theology than others,” the priest responded with a wry smile.

“Perhaps it is because your ideas look forward, and his only look backward.” Teilhard made no reply, so Einstein continued. “Anyway, the demonstration of the expansion of space made my Cosmological Constant unnecessary, my biggest blunder, I like to say. Not only was I wrong about Fr. LeMaitre’s work, but also about the need for the constant.”

Lippmann shook his head. “I’m not sure I see the connection to what we were discussing about science and certainty.”

“The point is, even with the perfect mathematics of General Relativity, which the eclipse in 1919 proved thanks to Eddington’s observations, mistakes can be made due to our limited understanding. We may still be wrong about expansion of the Universe as new observations are made.”

“As we discussed earlier, another example of the limits of the human mind and our dependence on our senses to provide additional, new data,” Teilhard added.

Lippmann shook his head again in disbelief. “You gentlemen are shaking my faith in human rationality being the way to create a better future.”

Einstein and Teilhard smiled at each other.

“This is why we leave room for something bigger,” Einstein replied with a twinkle in his eye.

Teilhard grew thoughtful. “It occurs to me that the reason I am more confident in God’s role in our destiny has to do with the differences in our approach to scientific reasoning.”

Einstein nodded. “Please, continue.”

Teilhard stroked his chin, deep in thought. Lippmann sipped his bourbon, fascinated. Einstein waited patiently. Finally, Teilhard looked up.

“Professor… Albert, I mean…your approach is fundamentally mathematical and deductive. You reason from mathematical postulates and arrive at theories that are universal and invariant. From these theories we can then make observations that either confirm or contradict the theory, and then you go back and refine your mathematics. Is that a fair summary?”

Einstein nodded. “Go on.”

“My approach, on the other hand, is to look backward at the record of life, the fossils, the geology, the miracle of all living things, and reconcile those facts with ideas about how nature changes through time. It is fundamentally a dynamic view of nature, looking at change and finding the directions of those changes. Certainly, we deduce relationships between fossils and how they illustrate evolutionary principles, but there is also a significant amount of induction, establishing larger principles based on the evidence. The combination of the vast infinities, the directionality of changes in nature, and the emergence of life from matter, and human intelligence from life, lead me, inductively, to conclude that we are experiencing a process of emergence, of movement toward some unity. With God, I believe.”

“Influenced, of course, by your own experiences of spirituality and your training,” Einstein added.

Teilhard smiled. “Of course. Perhaps what is different about our perspectives is that in the life sciences, everything is dynamic and changing, which is what fills me with wonder. For you, physics and math are searches for the processes that are invariant and always true to explain the material word. Isn’t it ironic that my interest in the dynamic aspects of nature lead me to the universal invariant of God, and your interest in the invariants of mathematics lead you away from God, at least a personal God.”

Einstein chuckled and shook his head. “Perhaps, Teilhard, perhaps. The difference may be only that I don’t feel comfortable speculating about the destination, even though you and I agree on the incompleteness of our current knowledge, and that there is a direction we are moving in toward more complete knowledge.

“Science is a tool but not a philosophy. There are philosophies that are consistent with a scientific approach but any philosophy that says, “there is no god” or “there is a god”, these are non-scientific statements. Science cannot contradict these statements because it just cannot address them. They are outside science. For myself, I have said many times that I believe the orderly laws of nature that science elucidates are, to me, an indication of a larger reality beyond human comprehension. Is this God? Perhaps. But that does not mean I believe in the personal God of organized religions. This is where Fr. Teilhard and I probably differ.” Teilhard nodded with a smile.

Lippmann raised his glass. “Gentlemen, this has been a most enlightening afternoon. I see that time has slipped away and I must be going. I thank you for your generous company and the wonderful conversation. You’ve certainly given me a lot to reflect on. I hope we can do this again soon.”

The others raised their cups and they toasted with smiles.

Leave a comment