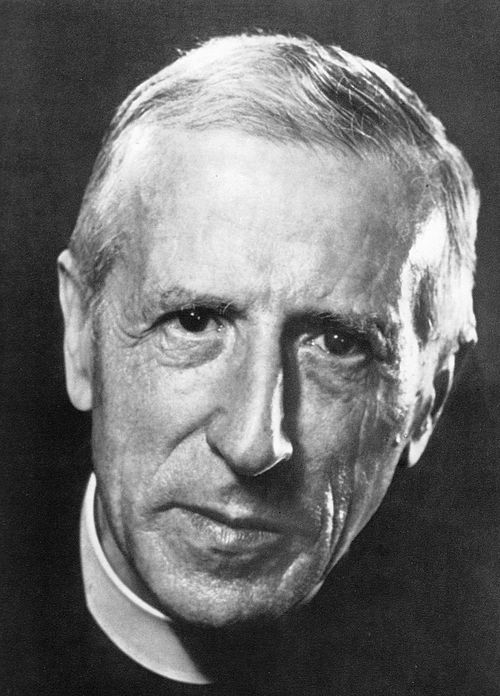

Walter Lippmann, one of the “fathers of journalism”, looks up as a slender man in black enters the bar and approaches with a smile. The Roman collar tells him that his visitor is Father Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. He raises his glass as the priest takes off his hat and overcoat and pulls up a stool next to the journalist. Lippmann gestures the bartender over.

“Please get Fr. Teilhard whatever he would like.” The bartender arched an eyebrow at the priest.

“Just coffee please.”

“Plain coffee, or something interesting?”

Teilhard gave Lippmann a curious look, returned with a shrug and a smile.

“Surprise me,” the priest replied to the bartender. He turned back to Lippmann. “I hope I didn’t keep you waiting.”

“Not at all. The train up from Washington D.C. was on time and I had a nice stroll in Central Park. I just got here.”

“Yes, I came through the park as well. St. Ignatius is just a few blocks away.”

The bartender delivers the coffee drink and Lippmann raises his glass.

“This is an unanticipated pleasure,” and they toast each other. “I’d love to continue our conversation about how your war experiences influenced your work.”

Teilhard nods and begins with their common experiences during World War I, when he served as a litter bearer and medic in the trenches for the French Army. Lippmann shakes his head in disbelief at the horrors the priest endured while he was safely behind the lines working on propaganda.

He began his Jesuit education at age 18 and took the first vows toward the priesthood at age 20. He was a brilliant student, and thanks to the influences of his parents’ interests, drawn to the natural sciences. He continued pursuing science with the encouragement of his Jesuit teachers and taught chemistry and physics at a variety of Jesuit schools.

In 1911 he was ordained as a Jesuit priest, and a year later, he began working in the French National Museum of Natural History studying paleontology. At the outbreak of the Great War, he was mobilized and served as a stretcher bearer, surviving many major battles such as the Marne, Ypres, and Verdun, among many others.

After the war, he continued his scientific studies, and became a leading Catholic proponent of evolution, based on his scientific work on early human fossils, influenced as well by his experiences of the suffering during the war.

In his writings, Teilhard talks about three infinities, of duration, scale, and complexity. Duration refers to the time scales we observe operating in the natural world, from the vanishingly brief oscillations of atoms and molecules, to the slow grinding movements of continents, to the lifespans of stars and galaxies. Human existence lies in the minutes to centuries part of that infinite time spectrum, but we know, thanks to the scientific method, that the natural world moves through time on much briefer and longer scales.

The infinity of scale refers to the sizes of things, from quarks to galaxy clusters. Teilhard worked in the field of paleontology and then anthropology, but these disciplines required a solid understanding of the advances in the field of geology. He examined the natural world from the scale of microscopic differences between fossils needed for proper classification, to the continental scale of tectonic plates and the layers of geologic strata necessary for the proper dating of fossil excavations.

“I’m familiar with the limitations of human senses relative to the immensity of the world around us,” Lippmann observes.

They discuss this intersection with Lippmann’s work. We can’t perceive these different time scales through our normal human senses. It’s only through the scientific method that we know these processes occur. Though there are limits to how we can naturally perceive the outside world, using our minds, technology, and the scientific method we can extend our senses and thereby increase the size of our perceptual bubble.

No individual human could appreciate these scales with their natural senses. With the aid of microscopes, maps, and the scientific method, a larger comprehension is possible.

The third infinity is of complexity. Teilhard sees an infinite continuum from the simple structures of atoms and molecules all the way up through the systems of the human body, to what would later be known as ecosystems, to civilizations.

Combining all three, Teilhard describes a universe of vastness far beyond individual human comprehension, but still something that was within grasp using the human mind and science. His awe of the natural world together with his many experiences of human suffering, led him, through his faith, to conclude that evolution is real, and that it has a direction, toward expansion of human consciousness, awareness of the infinities, and approaching union with God. This aligns with Lippmann’s ideas about the limitations of the human mind processing the sensory information from the outside world.

This is where mainstream scientists part ways with Teilhard. In philosophy, seeing or searching for a final purpose to a process is called teleology, and it’s Teilhard’s sin of teleology that keeps him from being considered by some a “real” scientist, despite his many scientific achievements and his relentless advocacy of evolution, which came with significant personal and professional cost. His writings were never published during his lifetime due to the restrictions the Catholic Church leadership put on his writings, and he was punished several times for his advocacy. Still, he persisted, sure that the science was true, and that it could be reconciled with his faith.

In summary, Teilhard draws a picture of the world consisting of infinities that the human mind, unaided, cannot grasp. Yet, we continue making progress understanding, controlling, and even shaping our world, despite our limitations. How can this be, how does it happen, and to what end? These are questions outside science, but they are important none the less.

Lippmann sipped his scotch. “This is why I’ve always been skeptical of the public’s ability to participate in meaningful decisions about ethics and morality.”

Teilhard raised his eyebrows. “That doesn’t sound very democratic.”

Lippmann nodded. “It’s a challenge, I agree. People need to be led to the right conclusions, the ones that maintain order and put society on the right track.”

Teilhard smiled. “But who chooses the right conclusions and how? I understand from your work that you don’t feel that religious institutions are well suited for that role.”

Lippmann opened his mouth to reply just as an elderly gentleman with a shock of unruly white hair entered the bar.

“Ah, the Professor has joined us at last.”

Next up: Albert Einstein. This will all make sense, I promise.

Leave a comment