One thing about writing in the SF genre is the challenge of constraining your speculations by what known science says is possible, or if you really want to loosen up, what might be possible. To do that, you have to get into the actual science quite a bit to make sure you know where the boundaries are. Cecelia Payne is one of the pioneers of astronomy that all writers of SF set in different solar systems are indebted to, whether they realize it or not.

Cecelia Payne, or Payne-Gaposchkin after she married in 1934, studied stellar spectroscopy. Her work transformed the field of astronomy, leading to many breakthroughs classifying stars and understanding the physics of their internal processes. Famous astronomer Otto Struve once called her first paper on the composition of stars “the most brilliant Ph.D. thesis ever written in astronomy.”

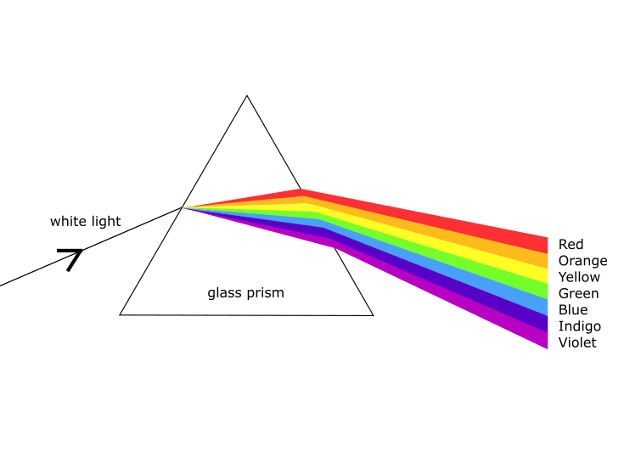

Spectroscopy is the study of how matter absorbs and emits light by measuring the intensity of light at different wavelengths or colors. Think of the rainbow produced by a prism hit by a ray of sunlight:

When the light that makes up the displayed spectrum passes through some other material, usually a gas, before spreading out, dark lines can be seen superimposed on the rainbow:

That pattern of absorption lines is unique for each element that is in the gas the light passes through, sometimes referred to as a ‘fingerprint’. Cecelia Payne had two brilliant insights: first, the heaviness of those lines is proportional to the amount of the element in the gas, in this case, of the atmosphere of the star being studied. Until her work, prior scientists had seen absorption lines in starlight for many of the same elements that the earth is composed of, so the assumption was that stars and planets contained similar amounts of the same elements. Dr. Payne showed that stars are mostly composed of helium and hydrogen.

Second, because of her familiarity with the emerging discipline of quantum mechanics, and building on the work of Indian physicist M.N. Saha, she realized that the pattern of loss of some absorption lines is correlated with temperature. This is because as an atom of a particular element contains more energy, it begins to lose electrons, becoming ionized. This in turn changes the pattern of absorption lines for that element at that temperature. Knowing the pattern changes, and at what temperatures they occur, enabled her to calculate the surface temperatures of stars, which had never been done before.

These two insights transformed astronomy, and lead to most of the current theories of stellar formation and evolution.

Why is this important for science fiction? If you are imagining an alien planet, populated by alien life forms, for really successful, detailed, and plausible world building, you have to establish some parameters. What kind of star does the planet orbit? How far away from the star is the planet? How old is the system? What kind of climate? The answers to these questions will determine what kind of life forms you can build on your planet.

For example, if you want to have your aliens living under a purple sun, you’ve got some work to do. Stars come in a limited number of colors: white, yellow, blue, red, orange, and maybe very dull red brown (whether life could exist on a planet circling a brown dwarf is a very open question; but not impossible!). But notice: no purple.

But we’re not finished! Maybe the atmosphere of the planet contains a mix of gases which might make the sun on the planet appear to be purple. Or, a blue star with something reddish in the atmosphere might appear to be purple.

Here’s the thing: the color of the star also determines some other things, all stemming from Dr. Payne’s work. Color means temperature, but color also determines the lifespan of a star. Hotter stars (blue) live shorter lives, cooler stars(red) live longer lives. Our Sun belongs to class G, the yellow stars, in the middle in terms of size and temperature, with a middling life span of between 8 and 12 billion years depending on the mass. Our sun is about 3.5 billion years into an expected 10 billion year lifespan.

Why is that important? The evolution of complex life forms takes time, so depending on how you want to populate your planet, you may need to take into account the age of the planet, and maybe the age of the solar system.

We’re still learning about our own biological history, so there’s lots of wiggle room, but still, it’s nice to know some general guidelines.

All thanks to Cecelia Payne!

Leave a comment